Museum Staff: An Investment Whose Protection is Overdue

Posted: December 2, 2019 Filed under: Learning Organizations, Museum, museum salaries, museum staff, Organizational Values, workplace diversity, Workplace Values | Tags: career, Leadership, museums 6 Comments

In the spirit of Thanksgiving, I hope you all read the letter from Esme Ward, director of the Manchester Museum (UK), published in Museum-ID Magazine. In it, Ward turns the fear-bound notion of returning objects brought or given to museums around the world from one of de-contextualization to one of connection. My favorite quote:

At their best, though perhaps all too rarely, museums can be spaces for identity-forming and truth-telling. They can ask “what is the story we tell ourselves about ourselves?” I believe that repatriation shifts the processes, language and thinking of the past towards a context of possibility and action for the future. Our museums can become places of genuine exchange and learning, reconciliation, social justice and community wellbeing.

You may think, nice, but that’s not my organization, but first, be sure. If you curate the collection of a wealthy white male, did he or his family travel? What did they bring home? Or if you manage collections in a general museum–the kind that functioned as a visible National Geographic for a small community–are you comfortable with the collection’s origin stories? But even more important, how can you as director, curator, or collections manager, shift the process, creating collaboration rather than a one-sided scenario where your organization puts a community’s stuff under vitrines and then tells their stories.

**********

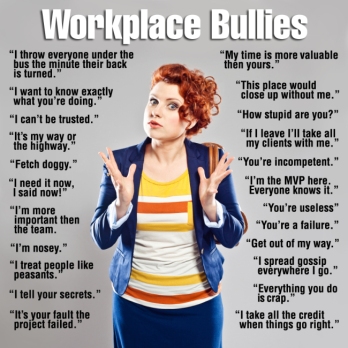

As you know I am not a Twitter fan, but this week I read a string of tweets prompted by @JuliaKennedy who asked for people’s most controversial opinions on the museum world. Her followers didn’t hold back. Comments ranged from ways museums discriminate against the disabled, to keeping too much old stuff, to decolonization. No surprise, there were any number of increasingly angry words about museum pay or the lack thereof, including unpaid internships, and fees to participate in museum volunteer programs. If you couple that with recent articles on museums and unions it’s a forest fire of discontent. Beginning with the Marciano Art Foundation, which became the poster-child for bad HR when it fired dozens of its front-line staff after they announced they planned to join the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSME), to The New Museum, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles, and the Frye Art Museum in Seattle, all now have staff who are union members.

Called a “movement not a trend,” by Artnet, the wave of unionization acknowledges the field’s wealth gap, which is most acute in the country’s large urban museums where front-line staff work for minimum wage and few, if any, benefits, while their directors may make 40 times that amount. Yes, the directors have huge, complex organizations to run. Yes, they do their jobs well. The judgement isn’t necessarily about them as humans. The judgement is about the gap, and the expectation that one person is compensated so well while everyone else should just be happy to be there, working an extra job or two to pay their student loans on the master’s degree the field requires as its entrance ticket.

Faced with unionization, leaders across the board, responded that museum culture is “special” and something unions can’s possibly understand. Mmmm. Really? Or is it just easier to ignore front-line staff’s issues rather than have a union force museum leadership to the table? This should be a warning call for all museum leaders. Yes, unionization is to-date confined to major urban organizations on the two coasts. But the problem of low salaries is endemic. You need only look at the Salary Spreadsheet created last spring. It now lists 3,652 postings from administrative assistants to assistant directors and more, and few are salaries you can gloat about.

As leaders isn’t it time you protect your investment in staff? They are, particularly if you also pay healthcare and some form of retirement, a huge portion of your annual budget. Assuming they’re good at what they do, don’t you want them to stay, to not spend idle hours at work trolling job sites, to be happy, to be creative? How can you not invest in them? Everybody wants a diverse workforce. It mirrors the communities we live in, and creates a better product, but a diverse workforce means museum staff is no longer the trust-fund generation or the my-partner-makes-six-figures-generation-so-I-can-afford-to-work-for $28,500-and-no-benefits.

Once again I call upon AAM to follow in the footsteps of the American Library Association whose professional companion organization, Allied Professional Association ALA-APA, adopted a minimum salary for professional librarians of $41,000 in 2007. (Side note: eight state library associations have their own minimums.) Why is this so hard?

Museum employees are the lifeblood of AAM, AASLH, and the state and regional museum service organizations. No one’s asking you to police salaries, only to stand with staff in acknowledging that the work we do, which is often awesomely wonderful, is worth more than we’re paid.

Joan Baldwin

Images: Screenshots of responses to @JuliaKennedy’s invitation to share “most controversial opinions on the museum world”

When Audience Members Violate Your Organization’s Core Values

Posted: July 15, 2019 Filed under: Diversity, Learning Organizations, Museum, Museums Are Not Neutral, Organizational Values | Tags: empathy, museums, nonprofit 1 Comment

First, a thank you to everyone who responded to last week’s post. Leadership Matters doesn’t receive a ton of comments so last week was a happy surprise. Many of you–especially Millennials and Gen-Xers– thought your point of view was missing, and sent examples. Clearly there’s more to say on generational collaboration and conflict in the workplace. We’re working on it, but if you’re drawn to this subject, and you’d like to write a guest post, let us know. Our email is leadershipmatters1213@gmail.com.

********

While questions of intergenerational workplace collaboration continue to simmer, we’d like to talk about a different sort of leadership challenge. This came to our attention through Laurie Norton Moffat, director and CEO of the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA. (Parenthetically, we should add something: Over the years we’ve ranted about how museum leaders need to read (and listen) widely–absorbing poetry, podcasts, science, philosophy, long-form journalism, novels, you name it—because it makes you more empathetic, broadens your perspective and helps you connect the dots in many unexpected ways. Moffat is that person. If what she posts on social media is a taste of what’s on her bedside table, screen and other devices, she’s an example to us all.)

This week Moffat posted an op-ed piece by Pamela Tatge, director of Jacob’s Pillow, Becket, MA. For those unfamiliar with “The Pillow” as it’s known locally, it is home to America’s longest running dance festival. Tatge’s piece details the interaction of a woman of color and members of the Pillow’s opening gala audience. Needless to say, it wasn’t good. The interactions were demeaning, objectifying, and horrifying. In fact, as Tatge reports, it’s a wonder the patron stayed for the whole event. What’s interesting here is Tatge’s reaction. First, let me say that everything I know about this incident is in her piece. There is nothing on the Pillow’s website, and only two dismaying follow-up letters in the Berkshire Eagle.

If a member of your audience insulted another visitor, how many of you would bare your organizational soul in the newspaper? The Pillow’s experience brings to mind the incident at Boston’s MFA in May where middle school students were subjected to racist comments by security guards and other visitors. In that case, reading between the lines, one of the most horrifying things was the sense that the museum might not have acknowledged what happened had the teacher not come forward on Facebook. In the end, the MFA revoked the visitors’ membership and banned them from the museum. In addition, it says it plans to provide additional training for guards in how they engage with visitors inside and outside the Museum.

One of the places organizations turn in crisis is their value statement. And while Jacob’s Pillow is curiously silent about Tatge’s piece on its own web site, it’s clear her actions were rooted in the Pillow’s Value Statement, which includes the following:

INCLUSION

We encourage a broadly diverse group of individuals to participate in our programs and join our Board and Staff, and insist on being inclusive of all peoples regardless of their race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, socio-economic background, physical or mental ability.

LEADERSHIP

We listen carefully, take the time to reflect on our successes and challenges, admit when we do not know something, and are accountable for our actions; recognizing that a crucial part of our role is to mentor the next generation of artists, arts administrators, and production staff.

Of the many issues on your 2019 leadership plate does audience behavior keep you up at night? What can and should a museum leader do to forestall racist behavior or hate speech in its galleries or heritage site? Is Tatge’s transparency the way to go?

Not that we haven’t written about this before, but here are some things to think about when your audience attacks its own:

- Use your value statement. Presumably you all–board, staff, volunteers–played a part in its creation, and live it day-to-day. Where else can your patrons read the values statement besides the web site? How often do board and staff talk about it? Is it clear to your visitors that your museum has a code of conduct?

- Silence is death. Don’t fetishize silence. Not saying anything will land you in a world of trouble. It will also make a mockery of your carefully crafted values statement. If you believe in something, stand by it, but have a plan.

- Think ahead. What steps should you take to ensure the right messaging in the event of controversy or crisis related to your organization and its values? Role play possible controversies to make sure your organization reacts as a team.

- Show some humility. Even if you aren’t the cause of the hurt, the hate speech or the racist comments, you are the venue in which they happened. Own what’s yours. If you hosted a cocktail party at home and one of the guests insulted another, you’d apologize wouldn’t you?

- Talk about these issues with your board. It’s easy to say what a museum or heritage site should do, but how (and when) does a board choose to discipline its audience, the very audience that is its lifeblood?

- Does your museum have a clear and easy way for visitors to let staff know when something bad happens? Once you say what you stand for (see the first bullet point), you have to provide the opportunity to express how the experience measured up. Help your staff learn to listen and respond accordingly.

A decade ago the glittery object among museum thought leaders was the idea of museums as a third space. As a concept–the museum as neutral ground where people gather and interact–is laudable if slightly utopian. But if the last 10 years have taught us anything, it’s that saying you’re the third space won’t work with a community clamoring for you to take a stand, to believe in something, and when appropriate, to say something. Hopefully museum staff, boards and volunteers agree on their common values, but your audience? It’s the wild card, the known-unknown you must court, charm, and cultivate. And what happens when the audience values don’t align with institutional values? If a visitor related an experience like the one Pamela Tatge heard, what would you do?

Joan Baldwin

Image: The National Liberty Museum

The No-Money-No-New Ideas Conundrum

Posted: April 1, 2019 Filed under: Creativity, Leadership, Learning Organizations, Museum, Museum Boards, Nonprofit Boards, Nonprofit Leadership, Organizational Values, Vision, Workplace Values | Tags: decision making, Leadership, museums, nonprofit, organizational learning 3 Comments

Two of my favorite myths at the beginning of Leadership Matters are: “We are the source of our own best ideas,” and “Anyone can lead a museum.” They come from a place that says museums are simple organizations doing simple stuff, and pretty much anybody can do what needs to be done. After all, there’s a gazillion books and YouTube videos. How hard can it be? I’ve never worked in a really big museum, but I know first-hand that among tiny to medium-sized heritage organizations and museums these two myths spawn a lot of problems, and the biggest may be they limit imagination.

You may have seen this type of behavior cast generationally–the proverbial eye-roll from older staff members when a Millennial suggests trying something new. Or it’s attributed to a particular subgroup within the museum, frequently with the pronoun ‘they’ — as in “It’s a great idea, but they would never go for it.” They refers to a nameless group of powerful people who make decisions for everyone else. Despite the fact staff may have no real understanding about the board’s decision-making process, ascribing blame in these situations is useful. Then there is the financial version, which goes something like, “I love that, but we just don’t have the money right now.” And last, but certainly not least is the version that combines one or more of the others: “We tried that before the recession, and it wasn’t that successful.” If your therapist were in the room for all these comments, she’d tell you you’re writing the script before anything’s happened. And she’d be right.

I’m not saying money isn’t important. It is. And it can buy a lot, and ease even more worries. But an organization can be really rich and also really boring. Surely you’ve been to some of those. They are beautifully presented, but stiff, still, and flat. There is, to quote Gertrude Stein, “No there there.” But there are other organizations where, without warning and often without huge budgets, you’re challenged, confronted by things you hadn’t thought about before or presented with memorable narratives. They are the places you remember. They are the ones that stick with you.

Imagination and ideas are a museums’ biggest tools. Otherwise you’re just a brilliantly-organized storage space. And yet how do you get out of the scarcity mindset? Practice. Truly. And start small.

If you’re a leader:

- Read widely. Listen and learn from a variety of sources. If you’re a scientist, read the book review. If you’re an art curator, read the Harvard Business Review.

- Model respect, and treat everyone’s ideas as doable even if they’re not actionable in the moment.

- Use the ideas that work now. Start small. What percentage of your guests are elderly? Will moving some benches afford a view and make walking from place-to-place easier? Try it. If it doesn’t work, move them back.

- Change is a muscle. Build strength slowly. Don’t over do it.

- Think about ideas as cash catalysts.

If you’re a board member:

- Model respect and treat everyone’s ideas as doable even if they’re not actionable in the moment.

- Know what matters. Understand your organization.

- Invite a different staff member to your board meeting every month. Ask them what they would do if you gave them a million dollars. Listen. (And ban the eye-roll.)

- Devote some time as a group to talking about ideas as opposed to what’s just happened, what’s currently happening or what will happen. How can you raise money for an organization if you’re not excited about what it’s doing?

- Think about ideas as cash catalysts.

If you’re a leader or a board member, you’re role isn’t to maintain the status quo. You want more than mediocrity, don’t you? You’re a change agent, and change doesn’t have to come in a multi-million-dollar addition. Sometimes it comes in a volunteer program that models great teaching, a friendly attitude and deep knowledge.

Yours for idea stimulation,

Joan Baldwin

P.S. Two items of note passed over our screens this week: Nikki Columbus, who was briefly hired by MOMA PS1, settled the claim she brought against the museum. Kudos to Ms. Columbus for following through on her claim which accused MOMA PS1 of gender, pregnancy and caregiver discrimination. It takes money, courage and will to take on a monolith, but in the end cases like this one set precedent for others. Second, the Guggenheim Museum joined Britain’s Tate and National Portrait Gallery in no longer accepting gifts from the Sackler family. The Sacklers, owners of Purdue Pharma, makers of Oxycontin, donated $9 million to the Guggenheim between 1995 and 2015. Aligning gifts with core values is a tricky topic so stay tuned.

Dissenting With Grace or What We Learned from John McCain

Posted: September 3, 2018 Filed under: Leadership, Leading Across Organizations, Learning Organizations, Museum, Nonprofit Leadership, Servant Leader, Workplace Values | Tags: Leadership, museums, nonprofit Leave a comment

This week, in the wake of Senator John McCain’s death, the news was filled with tributes and remembrances from his friends, colleagues and family. From the beginning it was clear those tributes weren’t partisan. They came from both sides of the aisle, perhaps none as succinct as Joe Biden’s, “My name is Joe Biden. I’m a Democrat. I loved John McCain.” What do any of these remembrances surrounding McCain’s death have to do with leadership? A lot actually.

One of the great truths about leadership is good leaders are confident enough to embrace dissension with grace. If McCain’s life taught us anything it’s that we should be passionate, we should care, we should love a good argument. But that the argument is about work, it’s about the place we serve, the museum we care about, and when it’s over, we reach across the aisle or the table, shake hands, share a drink or a raucous joke.

Too often leaders, particularly leaders unprepared for their role, can’t abide dissension. It rocks the boat. They can’t separate themselves, even in their own heads, from the organizations they serve. And that is an important distinction. While some days–the Sunday you wore your oldest sweat pants to the grocery store and ran into an important, and impeccably dressed donor aside–it may feel like you are your organization, you are not. You serve the museum. You don’t embody it. And it’s that distance that permits you to welcome dissension at the staff table.

And dissension is necessary. In eulogizing McCain, President George Bush said, “Back in the day, he could frustrate me. And I know he’d say the same thing about me. But he also made me better.” It’s not just you who needs to be better, it’s your organization. If secretly, you’ve made up your mind, know what you want, then have the guts to state it and stand behind it. Don’t waste your staff’s time by asking their opinion when what you really need is adulation. That might work once, but over time it wears thin. Staff stop offering ideas, and neither you nor your museum changes for the better.

Encouraging dissension and discussion is a great equalizer. It says to everyone in the room that all ideas have value, from the person hired last week, to the person who’s working on her BA, to the curator with the PhD. Encouraging staff to be direct and strong-willed means they won’t flinch if you are direct and strong-willed back. They understand it’s not personal, it’s about work. Allowing your staff to bat an idea back and forth, engenders trust. Why? Because it tells the participants you trust them. Discussion isn’t about who wins or gets her way. It is an act of creation with the museum’s best interests at heart. And that’s what we’re all after isn’t it? A better museum—right?

Joan Baldwin

Building an Empathetic Workplace Focused on Work

Posted: June 4, 2018 Filed under: Learning Organizations, Museum, museum staff, Organizational Values, Work Habits, Workplace Values | Tags: empathy, museums, nonprofit 1 Comment

The museum workplace is full of feelings: Success–you got the grant; terror–the second floor bath really leaked and your insurance deductible is that high; delight–a child told you this was the best school trip ever; accomplishment–you might actually finish cataloging that collection; anticipation–the fall benefit is tomorrow. All these feelings and emotions connect to work, but you’re not a product of artificial intelligence. You arrive every day with your own jumble of emotions, and it’s the moment where these two paths cross that we need to think about.

You’ve heard that oft-mentioned workplace trope, “We’re like a family.” Maybe. Strong families are committed. They communicate well and regularly. They are resilient. They share values and belief systems. They like spending time together, and they are affectionate. Those are all good things, although not all are workplace appropriate. In addition, not everyone working in your museum or heritage organization comes from a healthy family. Some arrive with a host of baggage. Advertising the workplace as a family sets it up as a place that fills a host of unmet needs. Work quickly becomes a spot where individuals feel comfortable discussing their failed relationships, their children’s problems or less dramatically, a venue where they let go of the frustrations of modern life. And while some colleagues share too much, others don’t share at all, yet their silence says everything. They can’t focus, are absent or on the phone frequently. When the over-arching culture says “We’re family,” it’s hard for museum colleagues (and leaders) to separate the hum of personal drama from the day-to-day at work or to know what level of help or participation is appropriate.

Once, a boss I didn’t much care for, an individual who met alcoholism head-on so he knew a bit about controlling feelings, told me that the hardest thing about work is exercising restraint. At the time, I brushed it off, but it’s stayed forever embedded on my personal hard drive, a home truth about saying less. That’s true both as a leader and a follower. It’s a reminder to all of us to create a museum culture for the public AND for staff that is warm, embracing and empathetic, but at the same time clear that our first priority is the communities we serve and the objects, living things and buildings we care for. In other words, work is about work.

Not being like a family doesn’t mean museum leaders can’t or shouldn’t address staff’s problems when they interfere with work. But here’s a caveat: Do your homework first. If you have an HR department, consult them. Know what you can and cannot say, and what you can and cannot offer, and whether HR needs to be in the room when you speak to your employee. Too often people suffer through massive personal drama because they’re ashamed of what’s happening to them. If you don’t have an HR department, use resources in your community — perhaps through your Chamber of Commerce — to get the advice and counsel you need. Make sure you’ve documented the employee’s behavior so you’re not offering vague descriptions that only add to the misery. If inattention costs your organization something, be prepared to explain. Work toward:

- Creating a climate where staff aren’t afraid to say they need to press pause.

- In the event of a personal tragedy, make sure staff know who to talk to.

- Remember that accident, illness or broken relationships can happen to anyone. Don’t blame an employee for circumstances beyond her control.

- Separate legitimate tragedy from a staff member who uses the museum to shed emotional load.

- Work with HR and your board personnel committee to understand what alternatives you might offer–sick leave, FMLA, short-term disability–and know what those mean.

- Build a museum workplace that is warm and empathetic, yet focused on work.

Joan Baldwin

You Are Judged: Bias and the Museum Workplace

Posted: May 21, 2018 Filed under: active listening, Communication, Community, Leadership, Learning Organizations, Museum, Nonprofit Leadership, Organizational Values, Workplace Values | Tags: Leadership, museums, nonprofit Leave a comment

Unconscious bias follows all of us around like a shadow. It’s not exclusive to people we don’t like or trust. It belongs to everyone. It comes to work with us every day. It’s there when co-workers chat over coffee, when we go to staff meetings and when we make decisions. It’s present when we interview new employees or volunteers. And it’s there any time we want to make change in the workplace.

Perhaps it doesn’t feel like your problem because you work with a homogeneous staff? Or perhaps homogeneity defines your part of the museum? Living inside a bubble doesn’t mean bias isn’t there. It just means you don’t experience it. And while much of today’s discussion tends toward race, bias is a searchlight pointed alternately at age, gender, weight, voice, education, class, and more.

History shows us life is iterative. A century ago white women struggled to gain museum leadership positions, but for people of color in 1918, even an assistant to the director position wasn’t a possibility. Today, the needle’s moved. Just not enough. We can see what’s wrong, and the data is there in case we need to have injustice confirmed by numbers.

And its not just museum offices where bias raises its head. Recently bias seeped into collections decisions–at the Brooklyn Museum where the well-publicized hiring of a white curator for the African collection spurred the Museum’s community to protest, and at the Baltimore Museum of Art where the decision to deaccession in order to purchase work from marginalized artists set tongues wagging.

Museum leaders and boards need courage. They will never be seen as working with communities if they aren’t brave enough to stand beside them against sexism, poverty and bigotry. Speaking out means risk, and many organizations feel they can’t afford it; the loss of a gift or board member is too dangerous to take a stand. But courage also demands hope, the hope that losing one gift might mean another arrives precisely because a museum or heritage organization stood up for what it believes.

Museums and heritage organizations absorb and reflect the world in which they function, and the world outside is frequently polarized. Should museum leaders take a stand? Yes. Noblesse oblige isn’t enough. The days of museums and heritage organizations doing stuff for communities are over. It’s time to work with them. But before museums can be value driven, their leaders and their boards, and, in fact, all of us need to listen to each other, however hard it is. We need the courage to call out truth, but once the words are said, it’s what comes next that matters. We need to wait for the answer, and listen again. It is exhausting, but naming bias and bigotry isn’t enough. In fact, it can further pigeon hole colleagues, community members or trustees. Perhaps the hardest thing about undoing injustice is understanding it’s not just about us. It can’t be solely about our personal narratives. It’s for all of us, and that requires understanding on everyone’s part.

What should museum and heritage organizations leaders do to change?

- Know your organization. Know your community. Know where your community and organizational values intersect. Be a bridge builder.

- Help your organizational leadership to model ways to change behavior without further polarizing a situation.

- Make sure your staff has a place to go if they are treated wrongly or unfairly. Make sure you and your board actually know what happens to staff who complain about bias or inequity.

- Don’t let diversity and community be social-media deep. Engage.

- Listen. Listen. Listen.

Joan Baldwin

Team Sports: Five Lessons for Museum Teams

Posted: May 14, 2018 Filed under: Communication, Leadership, Learning Organizations, Museum, Nonprofit Leadership, Work Habits | Tags: effective meetings, Leadership, museums, nonprofit, teamwork Leave a comment

Here is a simple truth: If you are a museum leader, you can tell your staff they’re a team any day of the week, but unless you make it mean something, the word “team” is just a random noun.

We think of teams as good things. They seem democratic. They flatten hierarchies. They bring people together. And, depending on how your museum or heritage organization defines victory, they’re sometimes winners. But if you have even a passing acquaintance with sports, you know some teams always deliver, and some never do, so it’s not about the name.

Recently I witnessed an incident where a department leader brought his team–his word not mine–together to plan a meeting of peer leaders. Although staff felt there was too little time to deliver a cohesive program, the leader wanted to push ahead. In the end, the event took place, and the leader ignored his team’s input, forgot to introduce or mention members of his staff, consistently interrupted others in their presentations, and made many believe they’d wasted brain power in planning for the event. Lesson one: Teams aren’t for everyone. As with so much in leadership, know yourself first. If teams and team work drive you crazy, you can opt out. We’ve all experienced the moment where–pick one–a board member, staff member, or volunteer misses a meeting and the chemistry changes. Discussion moves along. Decisions are made. Boxes are checked. If teamwork isn’t for you, let your staff plan. Go over the results with your assistant directors, make any changes you feel are necessary, and watch as they deliver the goods. Lesson two: Good teamwork, especially from the leader’s point of view, requires trust. Every time you authorize staff to act on your behalf, you say “I believe in you.” Say it enough, and they start to trust you.

Lesson three: If you’re going to lead a team, know where it’s going. In the scenario Leadership Matters observed, there was little understanding about why this presentation mattered, and if it did, why the team leader waited ’til the last minute to plan. If an event or grant application matters, be clear about why. Tell your colleagues why an event demands all-hands-on-deck, not because they’re dense, but because they deserve to hear it from you.

Teamwork doesn’t guarantee Nirvana. Productive teams often argue. Lesson four: Be prepared for push-back. Value your staff. Being willing to argue about something doesn’t automatically indicate staff hate each other (or you) or enjoy being disruptive. Instead, it may indicate they care about the museum and its programs. And yes, every team needs the one member who’s going to say the emperor has no clothes. Why? Because it makes everyone look at the question, project or event with new eyes.

Teams are about group, not individual, behavior. That’s why a soccer team practices drill after drill. Their individual skills are in service–literally–to the goal. Lesson five: If you’re a team leader, you have a role in helping the group do its best. That means for 30 or 45 minutes, it’s not about you. Instead, your role is to manage the team: To be positive and encouraging; To pull it back on task; To ask if things are clear and make sense; To make sure everyone understands their tasks; To ask the group to reflect on what they’ve done before pushing on to the next goal. And perhaps, most importantly, to decide what tasks are best left to individuals rather than the group.

Do you work in a museum where staff are referred to as a team? Is that a good or bad thing?

Joan Baldwin

What We’re Reading, Watching, and Listening To…

Posted: February 21, 2018 Filed under: Diversity, gender equity, Happiness, Leadership, Leadership and Gender, Leading Across Organizations, Learning Organizations, Museum, Museum Boards, museum career, museum staff, Nonprofit Boards, Nonprofit Leadership, Organizational Values, Professional Development, Volunteers, Work Habits, Workplace Bias, workplace diversity | Tags: advocacy, feminism, governance, Leadership, museums, nonprofit, organizational learning, transparency, workplace culture 1 Comment

Leadership Matters was on the road over President’s Day Weekend, heading south to the Small Museums Association meeting in College Park, Maryland. There, we talked about “Lessons from the Workplace: Women in the Museum.” We’ll be back next week to report on the audience reaction to issues of gender and the museum world, but in the meantime, here are some things that have captured our attention recently.

Books: Women & Power-Manifesto by Mary Beard. A short (128 pages), but blistering account of how women have been silenced throughout history. Don’t want to spend the money on the book? Here’s the backstory from the New Yorker: The Troll Slayer.

Managing People and Projects in Museums: Strategies that Work by Martha Morris. Morris rightly states that “The majority of work in museums today is project based.” So, why not combine the topics of projects, people, management, and leadership in one easily accessible book from a veteran museums studies educator? In addition to a whole chapter on museum leadership, Morris takes a deep dive into creating, managing and sustaining teams, including the team leader’s critical role.

Articles & Blogs: Not enough ethical challenges in your leadership life? Read this: The Family That Built An Empire of Pain.

#MeToo and the nonprofit sector: Vu Le is the fertile mind behind the blog, Nonprofit AF. If you’re not reading, you’ll want to make this one of your weekly must do’s. In the post we highlight here, Vu offers up his thoughts about creating safe environments for staff, volunteers, and community members. “We must examine our implicit and explicit biases,” Vu writes. “We need to confront one another and point out jokes and actions that are sexist. And we need to do our own research and read up on all these issues and not burden our women colleagues with the emotional and other labor to enlighten us.”

In this Harvard Business Review article, the fastest path to the top of an organization usually isn’t a straight shot. The authors rely on extensive research to explore why big, bodacious, and bold may feel counterintuitive sometimes, but are usually the keys to CEO success.

The Women’s Agenda is a regular shot of women’s empowerment reading from across the big pond (Australia, that is). News and research is gathered from around the globe on women in leadership, politics, business, and life.

Are Orchestras Culturally Specific? Jesse Rosen, League of American Orchestras president and CEO, recently led a discussion with four thought leaders about orchestras and cultural equity. From the intro: “While diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) are complex topics that require thoughtful consideration and strategic action, the concept of equity can be especially nuanced. It challenges us to fundamentally reconsider what it means for orchestras to play a constructive and responsive role in their communities—a role that acknowledges and responds to past and current inequities in the arts and in society.” Museums and other cultural institutions, take note.

Video: This video features CharityChannel’s Stephen Nill and members of the Governance Affinity Group of the Alliance of Nonprofit Management discussing their research on nonprofit board leadership. The discussion centers around a ground-breaking survey representing the second phase of research on this topic. The first phase, the widely acclaimed Voices of Board Chairs study, investigated the roles and preparation of board chairs, surveying 635 board chairs across the United States. Not only is there very little research that investigates nonprofit board chair leadership, but there is even less about other pivotal leadership roles within boards such as the officers and committee chairs.

You may think there’s not much connection between endurance running and museum leadership, but perhaps there is. Take a look at this video on how to run a 100 miles. Perhaps there are some parallels?

Sound: A big thank you to podcaster Hannah Hethmon who assembled all the museum-related podcasts in a handy link for us all: https://hhethmon.com/2017/12/31/a-complete-list-of-podcasts-for-museum-professionals/

Leader, Know Thyself

Posted: January 8, 2018 Filed under: Leadership, Leadership Development, Learning Organizations, Museum, museum career, Nonprofit Leadership, Self-Aware, Work Habits | Tags: Leadership, museums, nonprofit, organizational learning 1 Comment

It is a new year. Many of us made lists last week, recommitting ourselves to the “new year, new you” maxim, foregoing some things, while trying to develop healthier habits. If you’re in this mode, think about self-awareness, not just for you, but for your organization.

We’ve written a lot about self-awareness here as a grounding principle for good leadership. Being a self-aware leader means knowing yourself. That doesn’t mean knowing whether you prefer mint chocolate chip to strawberry. It’s more about knowing your strengths and weaknesses. Personality tests can help. If that idea makes your skin crawl, think of it as a way to understand your behavior rather than as a definitive description of who you are. One I’ve recently discovered is the Heart, Smarts, Guts and Luck test. It’s built for business leaders so some of the questions don’t apply to museum folk, and participating means you need to supply some personal information so if that’s not for you, there are other tests like Meyers Briggs or Predictive Index.

Self-aware leaders also check-in regularly with themselves and others. Some review the day’s activities every evening, analyzing what happened and what they might have done differently. Others review monthly. The idea is to learn–over time–how and why you make decisions. The third in this trinity is being aware of others. Whether it is your team, your department, your entire staff, as a leader, you want to build a team that’s diverse yet complementary. You can’t do that without understanding staff strengths and weaknesses. So…in a nutshell it’s about knowing yourself, improving yourself, and complementing yourself.

But…if you really want to make a difference in 2018, take that mantra and apply it to your organization. Does your museum or heritage organization know itself? Do you and the Board really understand your organization’s DNA? Do you check in regularly and review how and why major decisions are made? When the Board makes a major decision, does anyone record the reasons why? Does your organization discuss past decisions looking for similarities before finalizing new ones? Or do a few individuals decide while others look up from their cell phones and nod? And does your museum know who it is in your town, city and region?

Part of answering all those questions lies in data. If you’re not already a fan of Colleen Dilenschneider and her blog “Know Your Own Bone,” you should be. She is masterful about the how and why of data for cultural organizations. Susie Wilkening continues to conduct deep research about museum visitors and their motivations for engagement. They will teach you that data is just numbers if you don’t ask questions. And you need to ask the right questions. Too many organizations are the equivalent of data hoarders. They have numbers for everything, but can’t make meaning out of any of it.

It’s still early in what promises to be a challenging year for museums. Take the time to make change. Commit yourself to understanding your leadership DNA, as well as that of your organization, commit yourself to questioning your organizational decision-making process, and commit yourself to using data in a meaningful way. Don’t let your organization be guided by anecdote and opinion. Be a self-aware organization and know what you know.

Joan Baldwin